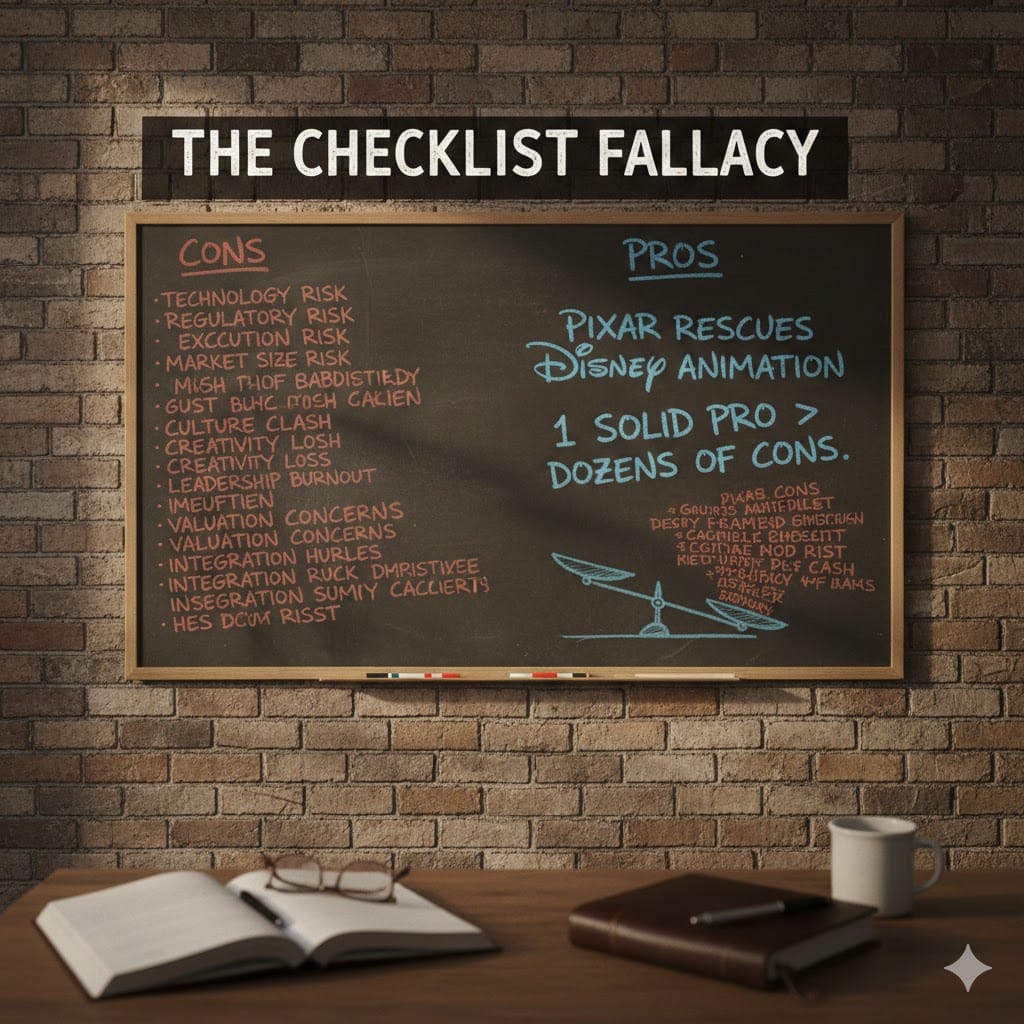

The Checklist Fallacy

Sometime in 2005, Bob Iger and Steve Jobs sat down in a room together to discuss Disney acquiring Pixar.

Iger recalled Jobs' initial reaction and the initial list of cons they laid out on the whiteboard in Cupertino.

- Disney will destroy Pixar's culture

- Disney will kill Pixar's creativity

- Fixing Disney animation will burn out Pixar leadership

And so it went.

Iger said the only pro was that Pixar could rescue Disney animation, which was on the brink after a five-decade run. But, ultimately, even he didn't see how it could possibly make sense.

Jobs responded, "even one solid pro can be more powerful than a dozen cons."

Of all the business books I've read, this story stuck with me not because of the optimism it conveyed, but because it made me think differently about risk in investing.

Every deal comes with the same list: technology risk, regulatory risk, execution risk, market size risk, and so on. If you give each one equal weight and count them all up, you'll never invest. But some of these risks are fatal. You have to weigh which ones would actually kill the deal.

Most investment decisions revolve around a diligence checklist and a financial model loaded with assumptions. They almost never come with the probabilities or weights needed to actually make a decision.

It's famously said that the stock market is a voting machine in the short-term and a weighing machine in the long-term. Investment diligence works the same way; you can vote on a risk or you can weigh it.

Voting means every risk gets equal consideration. We tally up the total, and if there are too many, we pass. Weighing means we identify the 1-2 risks that would actually kill the deal and assess those deeply.

The problem is that weighting requires judgment, and judgment is harder to defend than process. Risk is often subjective, hidden, and unquantifiable. Which means weighing risks isn't a mathematical exercise, it's a judgment one that's wrapped in ambiguity.

Since people love certainty, we often default to running through our checklist. It's very easy to mistake completeness for thoroughness in this case. "I checked all the diligence items off" is very different than ranking the risks in order of company-killing potential.

Steve Schwarzman and Sam Zell wrote two of my favorite business autobiographies, and for two guys who consummated one of the largest real estate deals ever, it's no surprise they shared a similar philosophy on this topic.

Jay taught me to use simplicity as a strategy. He had an uncanny ability to grasp an extremely complex situation and immediately locate the weakness. He always said that if there were twelve steps in a deal, the whole thing depended on just one of them. The others would either work themselves out or were less important. - Sam Zell

In my relatively short career, I had learned that deals ultimately come down to a few key points that matter. - Steve Schwarzman

And, by the way, I've only used risk here to keep the post simple. This is a two-way street.

A few strong pros can outweigh a long list of manageable cons. If you have deep conviction in a market, unique customer insight, or understand how you can add value better than anyone else, those weighted pros can win the deal. The ultimate goal of any investment exercise is getting to the correct risk-adjusted answer.

Every deal comes down to 1-2 points. That ability to simplify is itself a form of understanding. If you can't distill a deal to its core risks and opportunities, you don't understand it well enough to invest.

Ideas I'm Chasing

Probability is subjective.

In a multi-turn game, you don't want to be average.

Ideas I'm Collecting

"And it never failed that during the dry years the people forgot about the rich years, and during the wet years they lost all memory of the dry years. It was always that way." - East of Eden

"The monster that smothers potential comes wrapped in a nice, comfortable blanket." - Dr. Julie Gurner