The Moat Is Knowing What to Build

For the last year or so, I've been a skeptic of AI. Most of my research had been on the side of "what happens when bubbles pop" and reading about the aftermath of railroads (1873) and telecom/fiber (~2001).

From my experience, AI was mostly a better search engine, useful, but not revolutionary.

But, I firmly believe that the best investors stay curious, test assumptions, and play directly with the tools that could be generational shifts.

So, I began to play with Claude Code whose name is a bit of a misnomer. While it might primarily be built for software engineers, it applies to any knowledge worker.

My mind has officially been changed, or at the very least, awakened.

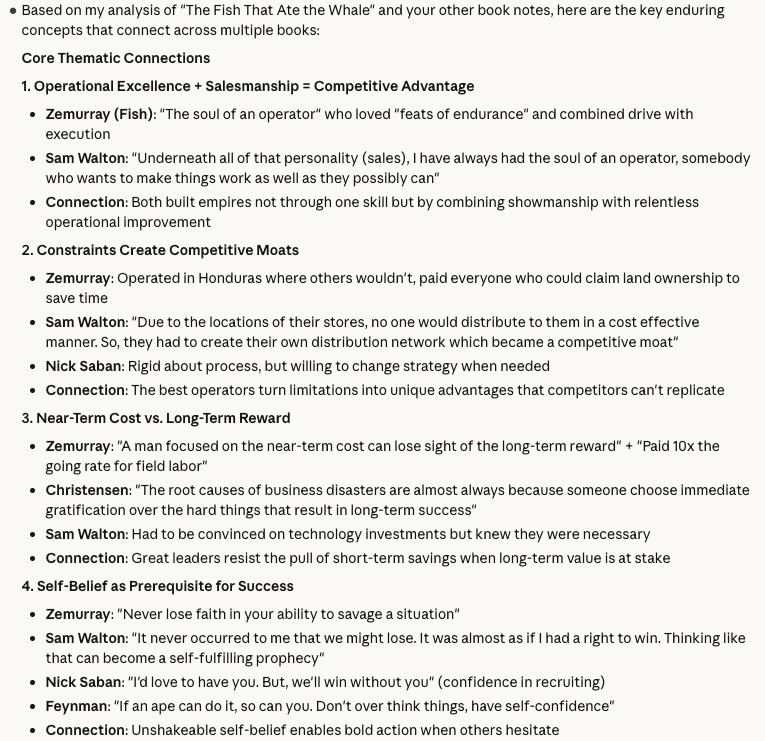

Over the holidays, using nothing but Claude, GitHub, Obsidian, a few APIs, and my Mac terminal I built a Chief of Staff and research assistant. Here's a simple example of what it can do:

In this context, the "so what" might seem to be missing but you don't have to stretch the imagination very far to see where this type of context is headed with practical applications.

"Claude, I've researched the grid for the last 5 years. From my notes, what's changed, what's the same, and what can you find on the internet that either supports or disputes my previous thinking?"

With a simple query like that one, the proverbial rabbit hole is blown wide open. And, that leads me to an important hypothesis that could define the next chapter of knowledge work and software development.

In the AI era, directing and managing agent work becomes the craft. Writing code is less like constructing a solution and more like setting up the conditions for good solutions to emerge.

The block was once technical knowledge, and it's quickly becoming customer and industry knowledge.

My dad spent decades as a lineman before becoming a COO managing grid infrastructure. Whenever I ask how he decides where to do proactive maintenance, he gives the same answer with the same gesture: 'It's all up here,' pointing to his cowboy hat. He's a human system of record with decades of pattern recognition compressed into intuition.

That intuition is what AI can't replicate. It can help extend it, scale it, even preserve it. But someone had to earn it first.

Building is mechanical now. Decent prompting skills get functional code out the door in days or weeks, not months or years.

But having a genuinely informed opinion about the right inputs, workflows, and outputs? That takes years of pattern recognition and listening to customers complain about the same things in twelve different ways (usually while insisting it needs to be fixed yesterday).

To build the research assistant that produced the output above, "coding" became more about prompting.

- Claude, I am trying to X

- I have access to Y tools

- My acceptance criteria are...

As a former product manager, this felt a lot like writing user stories except for myself. In this case I am the customer so I know what I am trying to accomplish.

I also had the advantage of keeping my notes in the same format (markdown) for 5+ years with a categorization framework that tied them together. That was a stroke of luck but leads me to believe we all need to think a lot more intentionally about the structure and quality of data we store moving forward because it makes AI that much more powerful.

I'm one of one, building for one. This problem is exponentially hard for organizations building to serve millions.

When building software was hard, you needed a technical specialization. Engineers, designers, product managers each contributed in coordinated but siloed ways. The friction created natural checkpoints.

Now, anyone can spin up a working solution overnight. These agents literally run while we sleep. Every person on your team can, and will, experiment. That democratization is exciting. It's also chaos waiting to happen.

The new organizational challenge isn't shipping faster. It's creating conditions where the right thing emerges from all that speed. Building can happen in days now. But forming a genuinely informed opinion about what to build? That's still a multi-year cycle of customer conversations, failed experiments, and pattern recognition.

Technologists have grown fond of the word 'tastemaker.' I'd propose a simpler definition: someone who knows what the customer wants, not because they asked once, but because they've listened millions of times - implicitly and explicitly.

The products that survive won't have the best technology or the biggest teams. They'll have the deepest customer knowledge. And they'll have created the conditions organizationally, not just technically, for that knowledge to compound.

In the age of AI, everyone can build. The moat is knowing what to build.

Ideas I'm Chasing

Process is the story. Results are the score.

The hardest problems need the widest aperture.

Ideas I'm Collecting

If you want to create a legacy, it's what you do after failure that matters. - The Greatness Mindset

Environment is the invisible hand that shapes human behavior. - Atomic Habits